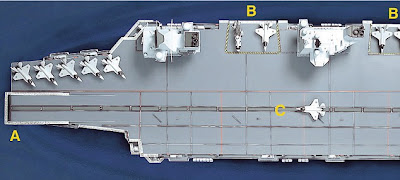

At first sight it looks like a giant Airfix model, with every detail carefully replicated, from the tiny fighter jets and helicopters to the unique twin ‘island’ control towers complete with a captain and commander to survey the deck. Even the 30mm anti-aircraft guns and the long-range radar have been painstakingly reproduced. At more than five feet long, the model is a carefully crafted reminder of our glorious naval past carved out of grey plastic.

Such vast aircraft carriers may once have been a badge of pride, but now you can’t help but feel they are merely lumbering relics of the Cold War or even the Empire, which have surely had their day. After all, the UK abandoned the idea of aircraft carriers in the late Seventies when our last big carrier, the HMS Ark Royal, was scrapped.

But this long hunk of plastic represents a work in progress. It sits proudly in the lobby of the design headquarters for the Royal Navy’s latest grand project. It’s a 1:200 scale model of what will be the two biggest warships Britain has ever launched – the 65,000-ton HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince Of Wales.

Each ship will have nine decks topped by a vast flight deck and will tower six metres taller than Nelson’s Column from keel to masthead.

‘Cover the flight deck with grass and it would be a par four,’ says one of the design team.

They will carry 36 state-of-the-art Joint Strike Fighter stealth jump-jets and four helicopters each, and be able to get 24 planes airborne within just 15 minutes.

‘All the major navies in the world are now building them,’ says Dr Lee Willett, head of the Maritime Studies Programme at the Royal United Services Institute.

‘The Russians have one of their big carriers, the Admiral Kuznetsov, back at sea and have stated that they plan to build 12 carrier battle groups. The Chinese and the Indians are also under way with plans, the Japanese are building a destroyer that will act as a helicopter carrier and the US are working on new-generation carriers.

‘We’re an island nation and we have global interests so we need these four acres of moveable sovereign airfield that we can deploy wherever we want, whenever we need them.’

What the building of the carriers also shows is that Britain is running out of friends.

Willett says, ‘The world is an unstable place and, post-Iraq and the global war on terror, access to other nation’s territory or airspace is more difficult.’

Former naval officer and now author Lewis Page agrees.

‘Friendly nations are hard to find and it becomes even harder once you have taken over local air bases, which are then vulnerable to attack.

'But there is a way to avoid giving yourself a logistical nightmare and becoming a target. Without having to ask anyone you can put an aircraft carrier 15 miles offshore in international waters and carry out operations from there without a single person needing to set foot on land or a single supply convoy coming under fire.

'And you won’t need to go through any diplomatic hoops.’

Despite the persuasive arguments, our two supercarriers have had a long and painful birth. The decision to build them was announced in the 1998 Strategic Defence Review, but the official signing ceremony only came a decade later, in July this year.

Now the Defence Secretary has announced the carriers will be further delayed – they are not expected to be ready for final delivery until 2016 and 2018.

Meanwhile, work continues at Rosyth dockyard on the Firth Of Forth to expand the granite sides of the massive Number One dock. It is here that the final assembly of the carriers will take place – or at least, that’s the plan.

But there are troubled waters ahead for this huge project, which still has the potential to go spectacularly wrong. Britain has never put together a ship in this way, on this scale, and there are fears over whether we have the commitment or the skilled workers to build the vessels to order and on time.

There have been criticisms of cost-cutting measures, concerns linger over whether the engines will work and, just to add to the uncertainty, the planes it is hoped will fly off the carriers have yet to be built.

From the outside it looks like any other nondescript provincial HQ, with a few well-manicured bushes and rows of family saloon cars parked neatly in front. But it’s on this unassuming industrial estate in suburban Bristol that the Royal Navy’s latest strike force is being designed.

Live has been given exclusive access to the design team, to watch them at work on blueprints and on computer designs for the new carriers, the UK’s most impressive piece of military kit for decades.

Within the open-plan office there are 180 people, among them 150 designers. I’m introduced to the design team in a meeting room, on one wall of which are pinned rows of detailed diagrams of the nine decks of the CVF (CV is the hull classification for a Carrier Vessel, while F stands for Future). We are prohibited from taking pictures as the diagrams are protected by the Official Secrets Act.

‘The project has been going for ten years and this is the third ship we’ve worked on,’ says naval architect Simon Knight, the project’s Platform Design Director.

‘We spent two years working on a bigger ship but found she was much too expensive, then a year on a smaller ship, but we couldn’t fit in everything we needed. We’ve been working on the CVFs now for the past three-and-a-half years.’

In the past, the team would have had to build life-size sections in plywood, but today most of the design and simulation is done on computers. Eddie Chambers, from Tyneside, is responsible for the intricate CAD (computer-aided design) 3D models of the ship. Built up in meticulous detail, these even show individual pipes and electrical cables.

He offers me a virtual tour of the engine room, then calls up one of the mess halls, complete with tables and chairs.

‘This allows you to walk around the ship,’ he says, ‘and means we can make sure that when we tell the build people to start they’ll know exactly where everything has to go. These ships are going to be huge, the second biggest in the world. Only the Yanks have got one bigger – and it’s good to know that at least we’ll have a bigger one than the French.’

Putting the ship together should be like assembling a Lego model. But with blocks of up to 10,000 tons

No single shipyard in this country has the infrastructure or personnel to construct the entire ship, so the plan is to build them in sections in different shipyards. Work on the lower bow section has already begun in Devon. The other shipyards are set to begin cutting steel in March 2009.

The aft block will be built in Glasgow, the central block in Barrow-In-Furness and the forward section in Portsmouth. The remaining upper sections will be constructed in smaller docks; bids from shipyards are still being considered.

The blocks will then be transported independently to Rosyth to be put together. The integration process is scheduled to take around two years and the plan is that as soon as the first ship floats it will leave and then work will begin on the second.

Putting aside questions over whether the money or political will could dry up before these carriers are completed, simply the practicality of gathering the parts together is a logistical nightmare.

‘Transportation is one of our biggest problems,’ says Knight. ‘Ideally you would build part of the ship in a dock, flood the dock, float the section of ship out and tow it to Rosyth, where you float it into another dock and let the water out so it’s left resting on blocks. You then connect it to the next section.

‘But unfortunately the aft section doesn’t float. We’ve looked at barges to transport it, but there’s only one big enough to take that weight and who knows if that barge will be around when we need her.

‘Alternatively we could put tanks on her to give extra buoyancy – basically enormous floats. But this is risky because we’ll have to tow it from the west coast of Scotland to the east coast.’

If and when all the pieces do finally meet, then putting the thing together should be like assembling a Lego model. But this is a massive undertaking – each of these gigantic blocks will weigh up to 10,000 tons.

‘Joining these enormous sections together, physically hammering them along a block and then making sure they’re exactly aligned will be a pretty hairy operation,’ says Knight.

The procedure has been carried out before to build offshore rigs, and the Navy is using it for its Type 45 destroyers, but those are small projects compared to these monsters. Each of these blocks will be bigger than a Type 45.

Even if things run smoothly this far, there are no guarantees that the ship will actually move. Simon Knight admits that nervousness will continue until the moment that HMS Queen Elizabeth finally goes into the water.

‘The speed trials, scheduled to take place off Rosyth, will certainly be nerve-racking. You can estimate how well the propellers will drive the ship forward, but until you’re full-scale in the water it’s very hard to know for certain. So when they first launch the ship, I’ll be terrified.’

The £3.9 billion cost for two carriers may seem huge, but they are built to serve for 50 years, and the budget is significantly less than for American carriers – each new ship costs $14 billion (£9 billion).

The project team admits that designing a ship with the desired features to a tight budget has been challenging. The result, they say, is notable more for simplicity and efficiency rather than hi-tech innovation. The most revolutionary element of the CVF design is its highly mechanised weapons handling system, which means a cut in the crew numbers required – from 4,500 on a US carrier (including a team of 150 just to move the weapons around) to 1,450.

One of the first things to go was nuclear power. Most modern aircraft carriers, including the American ships, are powered by an on-board nuclear reactor.

‘This is a brand-new ship, so getting through all the safety aspects of nuclear power would have been hideously expensive,’ says Knight.

Instead, like modern cruise liners, the HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince Of Wales will be propelled by electrical motors, powered by two Rolls-Royce gas turbines and four diesel generators. The diesel generators are more economical and used for general cruising, but when you need to get somewhere fast or need more headwind to help the planes to take off then you switch to the gas turbines.

Money has also been saved in side armour protection, though Knight insists this was a strategic rather than a budgetary issue.

‘The CVF’s first line of defence is the frigates and the new Type 45 destroyers around us,’ he adds. ‘Our only self-defence is close-in weapons systems and small guns. Instead, what you have on the ship is 36 of the most lethal aircraft ever made.’

That would be fine except that the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) jump-jets requested are still in early flight tests and engine problems mean they will not even attempt vertical take-off until next year.

‘It’s much easier with an existing aeroplane,’ says Aviation Design Manager Gary Davey. ‘Our ramp design has already been completed but the JSF’s undercarriage is still evolving.’

Areminder of the worth of aircraft carriers as mobile airfields was provided by the Falklands War in 1982. HMS Invincible and HMS Hermes had been built as ‘through-deck cruisers’, to carry hunter-killer groups of Sea King anti-submarine helicopters, which were capable of tracking down and destroying Soviet subs in the north Atlantic should the Cold War ever spill over into open conflict.

The four or five Sea Harrier planes also aboard were simply there to protect the ship from attacks by other aircraft. But then the ships were hastily reconfigured to carry eight Harrier jets in the Falklands crisis, and they proved invaluable in getting air power over their targets.

In these turbulent times, ‘power projection’ is once again considered a necessity. As complications over finding host nations and even getting agreement on using air space grow, so does the value of the carrier, which has been vital in the ongoing war in landlocked Afghanistan.

‘That started out as a carrier-based operation,’ says Dr Willett. ‘Finding shore bases can be politically difficult, and there’s also the question of whether they are of a sufficient standard. Upgrading them can be politically difficult and expensive. Carriers have proved their value in humanitarian and relief operations as well as in combat roles, and they remain a very flexible political and military asset.

Even if it’s not politically desirable to put troops ashore somewhere, you can fly aircraft overhead, use some ordnance against a specified target, or just deliver a warning simply by having a carrier parked offshore.

‘And you can do all this from your own sovereign territory in international waters and no one can tell you that you can’t.’

THE FLOATING AIRBASE

• The surface of the16,000sqm flight deck is covered in a grainy,heat-resistant paint,similar to very coarse sandpaper. The entire painted surface amounts to 370 acres - slightly bigger than Hyde Park.

• Two huge lifts, each with a 70-ton capacity, are capable of transporting two aircraft from the hangar to the flight deck in 60 seconds. The ship will be home to 36 Lockheed Martin F-35B Joint Strike Fighters and four EH-101 Merlin helicopters.

• The ground-breaking twin-island layout allows more deck space for aircraft and better visibility of the flight deck. The forward island is for navigating the ship; flight control is based in the aft island.

• The ship's 29,000 sq m hangar is 150 metres in length and has 20 slots for aircraft maintenance.

• There are 11 full-time medical staff on board managing an eight-bed medical suite, operating theatre and dental surgery.

• An onboard water treatment plant produces over 500 tons of fresh water daily.

• Two Rolls-Royce MT30 gas turbines and four diesel generator sets produce 109MW - enough to power a town the size of Swindon.

• Cabins are spacious and cruise-liner style, with en-suite toilets and shower facilities. Officers and senior ratings have single or two-berth cabins. The maximum number of crew in a cabin is six.

• The carrier will carry more than 8,600 tons of fuel, enough for the average family car to travel to the Moon and back 12 times. This gives a range of up to 10,000 nautical miles.

• Top speed will be in excess of 25 knots, sufficient to cross from Dover to Calais in an hour.

• The two five-blade propellers are each 30ft in diameter - that's one-and-a-half times the height of a double-decker bus.

The award-winning photographic pair were staying in Qaanaaq, about 800 miles from the North Pole, when the apocalyptic cloud colouring began over Inglefield Bay.

The award-winning photographic pair were staying in Qaanaaq, about 800 miles from the North Pole, when the apocalyptic cloud colouring began over Inglefield Bay. 'It looked apocalyptic and like a scene from one of the Lord of the Rings movies,' Mr Cherry said.

'It looked apocalyptic and like a scene from one of the Lord of the Rings movies,' Mr Cherry said. He said: 'I grabbed my cameras and photographed for about an hour as the cloud formation changed and the colour of the clouds turned from grey to pink as the rising sun's rays caught them.

He said: 'I grabbed my cameras and photographed for about an hour as the cloud formation changed and the colour of the clouds turned from grey to pink as the rising sun's rays caught them. Warning: Thousands have bought the fake toothpaste, which may be contaminated with harmful chemicals, at Boots and Sainsbury's

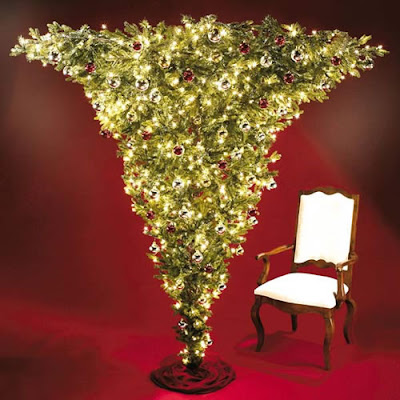

Warning: Thousands have bought the fake toothpaste, which may be contaminated with harmful chemicals, at Boots and Sainsbury's The upside of this upside-down 7-foot pre-lit Christmas tree is that you’ll have more room for presents underneath! This strange tree was originally designed for specialty stores to display ornaments while using as little floor space as possible.

The upside of this upside-down 7-foot pre-lit Christmas tree is that you’ll have more room for presents underneath! This strange tree was originally designed for specialty stores to display ornaments while using as little floor space as possible. In Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, the Grinch may have realized that Christmas doesn’t come from a store, but in this case, the Whoville desktop Christmas tree does come from one!

In Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, the Grinch may have realized that Christmas doesn’t come from a store, but in this case, the Whoville desktop Christmas tree does come from one! Good Grief! If Cindy Lou’s Whoville Christmas tree above wasn’t sad enough, maybe you’ll like this one: Charlie Brown’s Pathetic Christmas Tree as featured in Charles Schulz’ excellent comic strip Peanut…. This tree needs you!

Good Grief! If Cindy Lou’s Whoville Christmas tree above wasn’t sad enough, maybe you’ll like this one: Charlie Brown’s Pathetic Christmas Tree as featured in Charles Schulz’ excellent comic strip Peanut…. This tree needs you! It’s probably too late for you to start doing this one: the awesome Mountain Dew Christmas Tree. It took about 3 months of soda drinking (approximately 400 cans of Mountain Dew) and 4 days of building.

It’s probably too late for you to start doing this one: the awesome Mountain Dew Christmas Tree. It took about 3 months of soda drinking (approximately 400 cans of Mountain Dew) and 4 days of building.  Mountain Dew? Weaklings… Try Grolsch beer instead:

Mountain Dew? Weaklings… Try Grolsch beer instead:  If you’re into knitting and crafts, why not knit yourself a Christmas tree? Like this big one done by about 1,000 knitters at Eden Project

If you’re into knitting and crafts, why not knit yourself a Christmas tree? Like this big one done by about 1,000 knitters at Eden Project Don’t want to bother with shedding pine needles or the hassle of putting together an artificial Christmas tree?

Don’t want to bother with shedding pine needles or the hassle of putting together an artificial Christmas tree? Last year, Singapore jeweler Soo Kee Jewellery created this Christmas tree with 21,798 diamonds totaling 913 carats and 3,762 crystal beads. The tree looked like (and was actually worth) a million bucks!

Last year, Singapore jeweler Soo Kee Jewellery created this Christmas tree with 21,798 diamonds totaling 913 carats and 3,762 crystal beads. The tree looked like (and was actually worth) a million bucks! This is the mother of all Christmas trees: a gigantic 7-story "tree" made from 350 regular-sized artificial trees! Approximately 70 staffers of Yilong Media company of China constructed a steel framing and then stacked this pyramid of Christmas trees.

This is the mother of all Christmas trees: a gigantic 7-story "tree" made from 350 regular-sized artificial trees! Approximately 70 staffers of Yilong Media company of China constructed a steel framing and then stacked this pyramid of Christmas trees.

This increible bus stop was designed by Dennis Oppenheim in Ventura California

This increible bus stop was designed by Dennis Oppenheim in Ventura California  This bus stop allows skaters to go on a mini ramp attached to a bus stop, it's a Quiksilver ad

This bus stop allows skaters to go on a mini ramp attached to a bus stop, it's a Quiksilver ad Swing on a Bus Stop in London, part of Bruno Taylor's "Playful Spaces" art project

Swing on a Bus Stop in London, part of Bruno Taylor's "Playful Spaces" art project  Air-conditioned bus stop, presumably near Burj Al Arab hotel in Dubai

Air-conditioned bus stop, presumably near Burj Al Arab hotel in Dubai The Simpsons Bus stop in Germany, advertising for the movie

The Simpsons Bus stop in Germany, advertising for the movie This Star Wars "faux light saber" bus stop ad lights up at night.

This Star Wars "faux light saber" bus stop ad lights up at night. Soviet era bus stop

Soviet era bus stop This living room bus stop was created by Ikea as marketing for the Design Week 2006

This living room bus stop was created by Ikea as marketing for the Design Week 2006 Australia Post Bus Stop Advertisement

Australia Post Bus Stop Advertisement